|

| Image credit: Jessica Mullen |

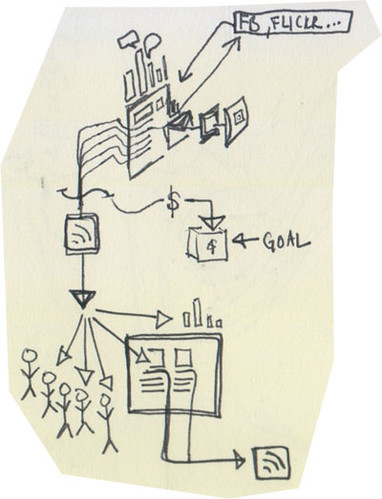

So it occurred to me that other translators might find it interesting and/or beneficial if I documented my own workflow, something I’ve honed over the years and that I now find pretty effective. Of course not everyone has the same client mix, faces the same workload, or uses the same programs, so your mileage may vary. I’d be happy if other translators chimed in in the comments.

File management

Let’s start with file management. I maintain a nested file hierarchy that goes something like: Year/Client/(Project Manager)/Project/files. I doubt this is particularly revolutionary. The normal file hierarchy for the current year and that of the previous year go into my Dropbox folder. (The free 2 GB account is generally sufficient for two years’ worth of files; after two years, I transfer the year’s files into my archives.) In my Dropbox folder, I also keep a separate folder—outside of the year-by-year hierarchy—called “Current Projects,” into which I place an alias (or, for Windows users, a “shortcut”) of all current project folders. This gives me quick access to the documents I’m working on: with a couple of keystrokes, I can be looking at all my current ongoing projects. And because it’s Dropbox, I know that my files will be synced between my desktop and laptop.

Workflow

As for workflow, when a client emails me a document, the first thing I do (after replying to say I’ve received the file) is hit the keyboard shortcut for “Save Attachments.” In the Save window, I navigate to the Client folder (and PM folder, if necessary), create a new folder for that project and save the file(s) in it. Once that’s done, I use another keyboard shortcut to automatically create an alias of the new project folder in the Current Projects folder. And finally, I open my to-do list (I’m currently using iProcrastinate, but I’m looking around for something more elegant) and enter the project name and due date. The beauty of this system is that with keyboard shortcuts (more on that in another blogpost), all this takes about 15 seconds, so it’s not burdensome in terms of time. This is important, because if you’re already working to a tight deadline, the last thing you need is to spend extra time fiddling with an inefficient workflow. If it takes too much time, there’s a chance you’ll put it off for later, and we all know what lies at the end of that tragic path.

Once the project is finished, I create an invoice and save it to the project folder for easy reference. After sending the completed translation and invoice off, I delete the alias from the Current Projects folder and mark the project as completed on the to-do list. If for some reason I don’t bill the client immediately, I don’t delete the alias and use a colour label on the folder to indicate that it hasn’t yet been invoiced.

I’m sure other translators have developed other systems, and as I mentioned earlier, I’d love to hear from you if you have anything to add or can suggest an improvement. Today’s global economic climate is putting pressure on translators to decrease or at least maintain rates at current levels; one way we can counter this is by increasing our productivity, and having an effective workflow is a step in this direction.